|

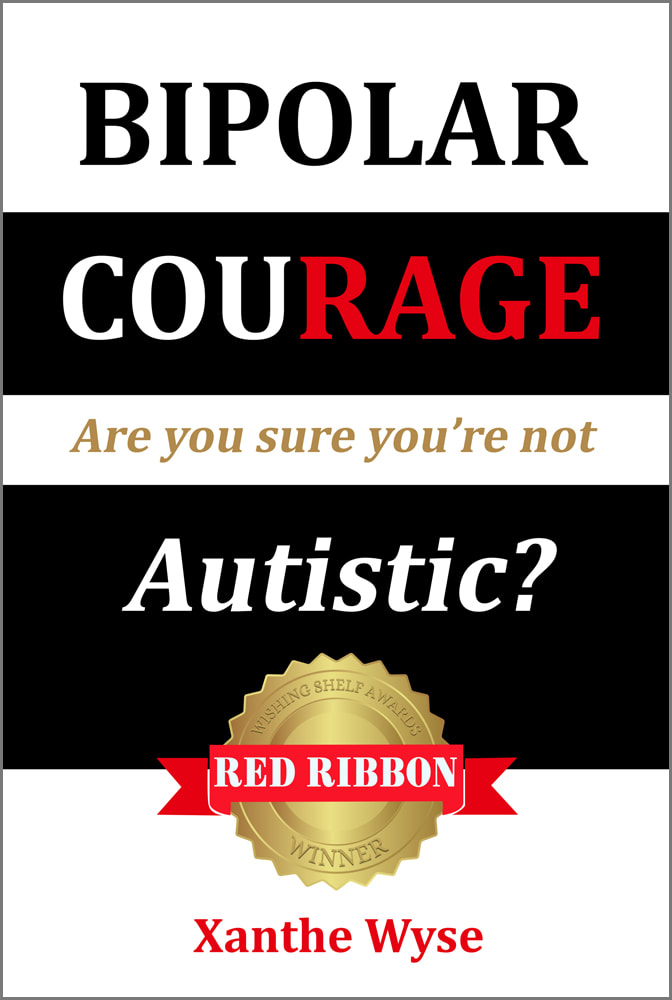

The ebook and paperback formats of my memoir, Bipolar Courage: Are You Sure You're Not Autistic? is already live on Amazon (all major platforms), just a few hours of publishing it. I'll link some of the main marketplaces at the end of this blog. There is a free app to read on any device, if you don't have a Kindle (I don't have one). I've included a sample chapter 1 in this blog post, free (I can't get the paragraph indents to align in this blog but they do in the books). It's an unconventional love story, in the world of autism and mental health advocacy. I was aiming to publish it in September, the beginning of a New Zealand Spring. I've done it! (Incredibly challenging with my disabilities). chapter one: Meeting Maxwell - free! When Maxwell Lock first spoke to me, I was a bumble bee on a bright yellow flower with a dark green background. Or at least my profile picture was, on a social media app I had recently started using. Instead of showing my face, my pic was one of my paintings, Spring. Maxwell had renown online; people seemed to be obsessed with him. My first impression was that he was intelligent, keen to debate and reactive. He made a scathing remark on someone’s dancing video: ‘Performative dancing videos don’t melt my heart, I’m afraid.’ ‘Hearts of stone don’t melt,’ I replied to him sarcastically. ‘Perhaps if you tried dancing, you would experience some joy instead of being so cynical.’ ‘You’re always attacking me,’ complained Maxwell. ‘I’ve hardly spoken to you. Some exaggeration.’ He conceded he was a grumpy old man 'trapped in a young man’s body'. His feisty, oppositional temperament with black-and-white views reminded me of my son, Zander. Maxwell said he had Asperger’s syndrome – a developmental disorder with difficulties with social and nonverbal communication skills. It was pretty damned obvious. ‘Asperger’s autism’ (that’s how the psychiatrist had worded it), was Zander’s childhood diagnosis. He’d had meltdowns over brushing teeth, showers, transitions, noisy malls, the sound of hand-driers and school. By meltdowns, I mean complete loss of control, with high-pitched screaming and physical aggression. He loved video games, but he could only handle a small amount of stimulation in one session, gradually building up a threshold. He'd gagged on some food textures, such as potatoes (unless very crispy, like shoestring fries with no fluffy centres). He’d insisted that his food was plain and separated, ‘with nothing on.’ We were often late to school, as he would be lining up toys in a trance-like state, not registering that anyone was speaking to him. Zander’s father, Craig, wondered if one reason he lined up his soft toys on his bed was to do a stock-take, to make sure none were missing. He’d get very attached to objects like empty food boxes. The school wouldn’t do anything about the bullying Zander was subjected to. So, I asked Zander who the ringleader was. He pointed to a boy with blonde curls. I went up to the boy and said, ‘You’re punching my son in the stomach and spitting in his face. Stop.’ I used a quiet voice with a tone that I’m sure conveyed, ‘You don’t want to find out what I’m capable of, you little shit.’ I didn’t actually know what I was capable of, but the boy stopped. Then, another boy called Zander names, so Zander punched him hard, giving him a black eye. Zander developed a school phobia and hid under the tables, lashing out at anyone who went near. He had bruises after being restrained by staff during a meltdown. He was excluded from school; it was obvious that school had failed him, anyway. Zander cried in distress at home; he wanted to die because he had no friends. It was then, his father finally said, ‘That’s it, I don’t care anymore if he gets a label.’ Craig had been resistant to getting Zander assessed. As Zander was in crisis, we went to a private children’s clinic, where he was assessed by a psychologist and a psychiatrist. This was back in 2010 (over thirteen years ago). We were initially recommended a stimulant and an antipsychotic for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, ADHD and a tic disorder. After I challenged the psychiatrist, she said that medications weren’t needed, after all. I’d been on a lot of meds myself and quite frankly, the side-effects sucked. So, I was worried medications might affect my son’s developing brain. I wanted to try child psychologists first. Asperger’s autism became Zander’s primary diagnosis. It was to try to get accommodations in school. A principal from a new school agreed to transition him gradually into school life; starting with some fun activities he could observe, then choose to participate in. He didn’t do full school days at first. He was matched with a non-authoritarian style teacher. We had to move house to be in the zoning for the school. I took him to psychologists and other specialists to learn self-regulation skills and to help with anxiety. Clinicians said to keep in mind that traits of ‘challenging-to-parent’ children can be valued later in the workplace. He was allowed to take himself away at any time, to calm. We bought a trampoline as that helped him to discharge some excess energy with repetitive movements. Most of his assertiveness and social skills training was done by me. I appealed to his logic rather than to emotion, as that was how he was inclined. Logical. He also didn’t like being told what to do, so I would make a suggestion, and let him come to his own conclusions. I enrolled him in Taekwondo classes to improve his self-discipline, confidence and physical coordination. When we arrived at his Taekwondo class, a boy was doing boxing training. Zander said in his stage whisper, ‘That boy is so fat!’ Instead of, ‘That might hurt the boy’s feelings,’ I replied, ‘That might be true but do you think it’s a good idea to say that out loud? Especially when that boy is wearing boxing gloves and can punch hard?’ There would be a pause, as Zander was thinking it over, processing it. His social skills training, my version, was mainly to learn to zip it. Rather than to blurt out what was on his mind, in that exact moment, to that particular audience, unfiltered. ‘Do you think it makes your life easier or harder when you call your teachers stupid to their face?’ I asked. ‘But I can’t help it,’ said Zander. ‘It just comes out. They are stupid.’ ‘How about muttering it under your breath when they’re out of earshot? Or come home and tell me?’ I suggested. Zander would think over what I’d recommended, not demanded. I let him come to those conclusions himself, rather than me telling him what he must do, as he was very oppositional. I enjoyed the philosophical discussions we had in the car when I picked him up from school. I didn’t enjoy aggressive meltdowns though, which could be accompanied by shouting and whacks to the back of my head with a shoe. Zander and I, both introverts, often sat quietly side-by-side on the couch, doing our hobbies on a laptop or tablet. Craig, a socially orientated extrovert, came home from work and said ‘Why are you both glued to screens? Why don’t you pay attention to me?’ Craig also complained that Zander and I were ‘cold’ in that we weren’t emotionally demonstrative – our emotions weren’t on display outwardly at all times. I worked hard to help Zander develop skills to help him to succeed with making friends. Anxiety was a big factor behind his meltdowns and other issues. I asked him, when he was calm, what a meltdown was like. He said, ‘It’s like my head is under sand. I can’t hear what people are saying.’ He also said he didn’t realise he was hitting and kicking during meltdowns. The early input with Zander paid off. He went from no friends to having some friends, a girlfriend and a job. When he was older, he said, ‘Thank you, Mum, for taking me out of that school and for teaching me to respect animals.’ I’d taught him to ignore timid animals initially and let them approach him first. Waiting to give them attention when they were ready to receive it. Zander and I have been separated, living in different countries, since around his twelfth birthday. He’s visited a handful of times. I had no choice but to return to New Zealand after a mental health crisis, after my marriage breakup. My drive to have a voice and my artistic expression has mainly come about to process my grief of being separated from my son. Trying to heal my broken heart. I’ve missed out on Zander’s teenage years. He’s gone from insisting on plain foods and separated foods to liking the hottest curries. He still refuses to eat vegetables, though. I started advocating independently online, as Bipolar Courage, back in New Zealand. I chose this name because it takes courage to live with bipolar disorder and bipolar gives me courage. I was stuck with bipolar disorder but I wanted to kick trauma’s butt. I take medications to help manage bipolar disorder. I’ve been in therapy with a clinical psychologist to treat post-traumatic stress disorder, PTSD, for over four years. My unpaid advocacy included a blog, vlog and a few other social media platforms. Social media is a mixed bag, with opportunities for connection plus abuse. Sometimes, there were words of encouragement. ‘You matter, Xanthe. You have a purpose. Your art and writing make people feel something.’ Someone said this when I was down after being attacked by strangers. Angela was watching my process videos doing a painting, after I’d been triggered when strangers had tried to force their labels onto me. Angela was curious about the concept of art as therapy, which was a theme for both my solo art exhibitions. She had befriended me on the app and we quite often chatted with private messages. Angela said she was autistic, more specifically diagnosed Asperger’s syndrome, in middle age, well after I thought her country had switched to the DSM-5. She admitted that she didn’t fully meet criteria, yet said she still got a diagnosis. In our chats, she said she’d wondered if she had bipolar disorder. Ebook linksNearly 3 full chapters (10% of the content) can be read for FREE from the ebook/kindle on Amazon. The ebook version is easier to read as a preview. Click on the 'read sample' link by the cover on Amazon. Bipolar Courage: Are You Sure You're Not Autistic? is now available from all major Amazon marketplaces including: Paperback LinksA paperback version is now available on Amazon. Check the 'look inside' linkd by the cover, on Amazon, to see some sample pages and chapters. Some links:

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Xanthe Wyse('Zan-thee Wise'). Disclaimer: the author of this blog is not an expert by profession and her opinions should not be taken as expert advice.

Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed